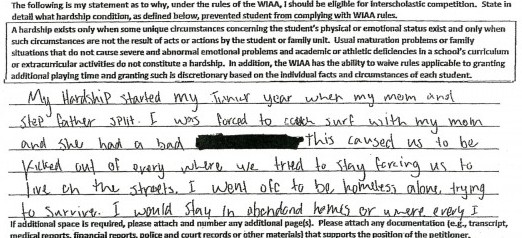

Homeless students drawn to Seattle schools by sports are often cast aside when the season’s over

This story is part of The Seattle Times' Watchdog reporting.

Photos by XX / The Seattle Times

Sixteen years ago, the federal government passed a law aimed at creating a bit of stability in the lives of homeless students. Kids whose families lacked a consistent address, migrating between shelters and friends’ couches, could sidestep standard residency requirements and remain at one school despite their transient lives.

But for a growing number of Seattle athletes, the intent behind the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act has been turned upside down.

For these ballplayers, homeless-student status allows them to move from school to school, following celebrity coaches and dreams of sports stardom while excused from rules that bind other athletes — such as maintaining a solid grade-point average.

Framed as an important opportunity for kids in need, the law also has been used to exploit their hopes. Because when sports end, many of these students find themselves adrift.

Last fall at Garfield High School, a quarter of the football team — including many of its top scorers, receivers, rushers and punt returners — were listed as homeless, according to school records. The designation allowed a half-dozen to play despite grades so low they otherwise would have had to sit out.

Another five had transferred onto the team so recently that, without homeless status, they also would have been ineligible for a season.

Many of these students are from severely troubled backgrounds. Some have been wards of the state or had parents in prison. And they are black. In short, exactly the kids that Seattle Public Schools — with its renewed focus on racial equity — says it is particularly concerned about.

A Seattle Times story in April highlighted the case of one such youth. A Seattle school district investigation followed that showed no violations, but nevertheless prompted the School Board to acknowledge wider problems with its oversight of homeless athletes.

For a handful of students, the chance to play at a well-resourced high school like Garfield, under a coach with NFL credentials, has led to scholarship offers from Division I universities, the primary pipeline to a pro-sports career.

But coaches, former players and several district officials say high schools in Seattle have used student athletes, teaching them how to gain McKinney-Vento status but offering little support when the season is over. A recent basketball star from Garfield, for example, is in jail; two standouts from Ballard football have been in and out of prison; and numerous marquee athletes from both schools have failed to make it through four-year colleges.

All transferred onto those teams under homeless-student status.

A Seattle Times analysis of student transcripts, homeless rosters and other district records, plus interviews with more than two dozen educators, coaches, parents and players, show that:

• Over the past four school years, the number of Seattle football and basketball players deemed homeless has soared from 49 in 2013-14, to 129 in 2016-17, a 163 percent increase — double the growth in homeless high-school students overall.

• Homeless student-athletes attend every traditional high school in the city — Ballard, Chief Sealth, Cleveland, Franklin, Garfield, Ingraham, Nathan Hale, Rainier Beach, Roosevelt and West Seattle — though not every school has come under question.

• Of the 15 McKinney-Vento athletes on Garfield’s football team last fall, two hailed from as far away as Texas and Louisiana. At least four hadn’t passed a math class in years. Three squeaked by with a string of D’s.

“Someone’s greenlighting kids to play who can’t even go to college because they don’t have the grades,” said Derek Sparks, a former football coach at Garfield who experienced something similar as a student athlete in California. “They’re using kids who are chasing the dream of being professional athletes, by hiding behind a law for homeless students — it’s just wrong.”

Chances running out

Homelessness, as defined by Washington’s schools, does not necessarily mean living in a tent under a bridge or along the side of Interstate 5.

Aiming to help as many transient students as possible, the law covers any who lack a “fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence” — including kids who shuttle among the homes of various friends and relatives.

DeeShawn Tucker, a basketball star in Seattle three years ago, received the designation after his father, with whom he’d lived in Federal Way, was murdered outside a motel.

Tucker’s mother lived in Seattle, but the two did not get along. So, Tucker said, he moved into another home near Garfield High and spent his senior year playing alongside four other starters — also listed as homeless — all of whom had transferred onto the team. They went on to win a state championship.

Now 21, Tucker recounted this history from the King County Jail, where he is awaiting trial on two felony burglary charges, and still envisions a professional sports career.

But Tucker was clear: He had planned for a university scholarship and settled instead for a junior college in Georgia, hoping to improve his prospects. “Then I got caught up in this mess,” he said.

The same pro-sports dream has driven Carrington Henry, 17, for the past three years. A McKinney-Vento football player at Garfield much of that time, only now does Henry grasp how slim his chances are. His grades are “pretty bad,” he said. His SAT scores place him in the sixth percentile of all students, and his library tutoring sessions wane after football season.

“I can’t blame anyone besides myself,” said Henry, who has lived under state care and in and out of motels throughout his youth. “My only chance now is to try and scrape up as much money as I can and go to junior college. Maybe I can walk on at a university.”

While The Times received information largely from educators and parents concerned about Garfield and Ballard, other evidence suggests that the problem is much broader. (The newspaper is naming only those students who consented to interviews.)

One football star, records show, enrolled at four high schools in four years, bouncing from Kennedy to Chief Sealth to Ballard and, finally, Garfield, where he arrived last fall alongside his coach from Ballard, Joey Thomas.

Under state rules, athletes who transfer between schools must sit out one season — except those with a “hardship” exception. Records show that the defensive player, whose most recent listed address was a Belltown homeless shelter, played all four years.

Under state rules, athletes who transfer between schools must sit out one season — except those with a “hardship” exception. Records show that the defensive player, whose most recent listed address was a Belltown homeless shelter, played all four years.

In at least four other Garfield cases since 2014, young men became homeless because they left families in other states and traveled thousands of miles in hopes of playing sports in Seattle.

One was Xaeyante Owens, 19, who dropped out of Central High School in Baton Rouge, La., as a junior and showed up on the Bulldogs’ field last fall listed as homeless. He played defensive back all season, pining for a football scholarship he was nowhere close to winning.

Another was Will Sanders, also 19, who arrived at Garfield from Beaumont, Texas, saying he had come to play ball after talking with Coach Thomas and a team-affiliated parent who painted Seattle as an opportunity to start fresh. Sanders’ grades were poor, and he had no family ties to the city.

On school records, a guidance counselor noted that the teen’s marks were so bad he’d need to earn straight A’s and B’s in six courses — plus another online — to compensate for earlier failures and maintain eligibility for the Bulldogs.

But then Sanders received homeless-student status and, with grades nowhere close to clearing the necessary benchmarks, remained on the roster, though not as a starter.

“I think he’s mainly here for football,” the counselor wrote.

In lackluster grades and multiple high schools, Sanders had company on the team.

District records show that one of the Bulldogs’ defensive leaders performed far below the required 2.0 GPA most of his junior year, failing math and chemistry at a West Seattle high school. Yet he transferred to Garfield as a senior last fall, was listed as homeless and played all season.

Similarly, a linebacker failed world history and Spanish as a freshman, earned D’s in algebra and literature and, as a junior, flunked chemistry. But, listed as homeless, he remained a Bulldog.

A question of oversight

Based on Sanders’ story about being encouraged to leave Texas and play at Garfield, Seattle Public Schools investigated, and dismissed, claims that school staff had broken illegal-recruiting rules.

The resulting report — limited by the refusal of at least four sources to speak with investigator Philip Thompson — nevertheless confirmed “a body of evidence that casts doubt” on the validity of home addresses provided by “some of the high profile athletes who have transferred to Garfield,” Thompson wrote.

“A lot of people say there’s more to this story,” Deputy Superintendent Stephen Nielsen acknowledged, noting weaknesses in the system for verifying whether students are, in fact, homeless.

“The main thing we want,” Nielsen added, is to make sure they “aren’t being used and abused.”

That question bitterly divides current and former athletes in Seattle, particularly within the African-American community.

Coach Thomas has declined to respond to questions from The Seattle Times, and Garfield Principal Ted Howard has said the district’s investigation was an effort to target his all-black football staff.

The Seattle King County chapter of the NAACP agrees. In May, President Gerald Hankerson sent a letter to Seattle Superintendent Larry Nyland and every member of the School Board, calling the investigation “an internal witch hunt” that is part of a pattern of “disparate treatment of African-American employees.”

“How do you distinguish the difference between helping a kid and a recruiting violation?” Hankerson said in an interview. “These brothers are walking a tightrope. I don’t even think a coach can give a kid bus fare without being accused of a violation.”

But other African-Americans, including coaches, former players and a school district official, are outraged at what they see as willful blindness toward the kids at the center of it all — who are black, too.

The School Board was concerned at the ease with which Sanders obtained homeless status, which is one reason it voted this month to reinforce requirements that all such students be vetted through the district office. While most are, athletic directors could also apply that label without informing headquarters.

With hundreds of players listed as homeless over the past four seasons, the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association (WIAA) has held eligibility hearings for 12. Only one student was denied, for failing to demonstrate that his situation was sufficiently unusual.

Eric McCurdy, Seattle’s head of athletics during this time, acknowledged holes in the system that could be exploited.

“We’re going to have to take a harder look at how McKinney-Vento works, no question about it,” he said. “There’s some potential to manipulate this because when someone’s McKinney-Vento it’s like, ‘hands off.’ ”

Part of the reason, McCurdy added, is sensitivity about the high number of black youths who have that designation.

Decentralized oversight from the WIAA further clouds the picture. Washington is divided into nine sports districts, each with its own eligibility officers.

Mike Colbrese, who sits at the head of the operation, said, for example, that he has not read the investigator’s seven-page report on Garfield and does not plan to.

Mike Colbrese, who sits at the head of the operation, said, for example, that he has not read the investigator’s seven-page report on Garfield and does not plan to.

“It’s not within my responsibility at this point,” Colbrese said. “We’re a bare-bones staff. We don’t have time to investigate or run rumors to the ground. The member schools are responsible for, in a sense, policing themselves.”

Members of the Seattle School Board, however, think it’s time for action.

“Clearly, this is like a boil that needs to be lanced,” board member Jill Geary said. “I’m not sure that our kids aren’t being manipulated and used for adult glorification.”

“Used and disposed of”

Colbrese maintains he had no idea about the number of homeless athletes moving from school to school. But that fact has not escaped parents and teachers.

Several in Ballard describe a trio of football players who transferred over from Bishop Blanchet High two years ago and stayed with various team parents.

“All of those kids were African-American, none lived around here and they weren’t given much beyond the opportunity to play football,” said a sports-minded dad, who insisted on anonymity and acknowledged providing one of the boys a bed from time to time.

“Of course, I knew it was all illegal. But these kids didn’t have two nickels to rub together. It seemed like they were just being used and disposed of.”

The practice of importing talented players is not new. In 2016, Bellevue High was sanctioned after an investigation found that the school was playing athletes with false addresses, among other violations.

Ten years earlier, the Chief Sealth girls basketball program was stripped of two state titles for similar reasons.

An assistant coach who worked at Ballard between 2010 and 2012 said that school’s football staff knowingly exploited homeless-student rules to stack the team.

“It was kind of an offhand conversation — there were kids we wanted from other schools, and we were trying to figure out how to do it,” said Daryl Brown, a defensive line coach under Joey Thomas. “If there’s any kind of issues at home, you don’t have to describe them. You just say there are issues. Or you can have them live with a family in your district, and that’s what we did with all those kids.”

“It was kind of an offhand conversation — there were kids we wanted from other schools, and we were trying to figure out how to do it,” said Daryl Brown, a defensive line coach under Joey Thomas. “If there’s any kind of issues at home, you don’t have to describe them. You just say there are issues. Or you can have them live with a family in your district, and that’s what we did with all those kids.”

Brown was dismissed from the job in 2012. He believes it was because, after a crisis of conscience, he voiced his concerns to McCurdy, the district’s athletic director.

Seattle Public Schools says he was fired for missing a week of football practice without permission.

But many of Brown’s claims are mirrored in the experience of former high-school athletes around the region.

Walter Jones is one example. He bounced between four Seattle schools during the 1990s — from Franklin to O’Dea (which is private), then Nathan Hale and Garfield — playing football as a homeless student.

“It’s not just Garfield, it’s systemic,” Jones said, describing an itinerant adolescence, recruited by coaches who told him how to work the system. “They told me, ‘If you want to be eligible, we’ve got to claim you as homeless.’ ”

Legally emancipated from his mother at 15, Jones (no relation to the legendary Seattle Seahawk) was indeed adrift. But he felt safe enough living with friends. His would-be coaches advised him to tell a different story.

“You say you’re sleeping on the streets, living in a car, whatever. They coached me up on how to do it,” he said.

Jones did not make it through college and today works as a personal trainer for young athletes. He often ponders his old mentors’ motivation. It was complicated, he believes, aimed partly at helping a youth in need, partly at improving their win-loss records.

A teenage pawn

For kids in rough straits, like Jones, sports can be a powerful incentive to stay in school. Yet the line between opportunity and exploitation is easily blurred.

Sparks, the former Garfield coach, recalls his own past as a student athlete with scathing terms. Recruited from small-town Texas to play high-school football in California, Sparks — the son of a single mother, raised in public housing — suddenly found his every need covered.

Sparks, the former Garfield coach, recalls his own past as a student athlete with scathing terms. Recruited from small-town Texas to play high-school football in California, Sparks — the son of a single mother, raised in public housing — suddenly found his every need covered.

“I had money in my pocket, a place to live, three cars to drive — and I was 15 years old,” he said. “I’d been a broken young man, but with the football in my hand I grew 10 feet tall.”

It was dazzling, until Sparks decided he’d become a teenage pawn in a world designed primarily to benefit adults. Several were members of his own family, who snagged positions and perks wherever they enrolled Sparks to play.

Months after graduating, he sued one of those schools for $40 million, charging that they’d manipulated his grades to punish him for transferring. The case settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

Sparks, currently coaching at Kennedy Catholic High School, is now reliving those years from the other side. After a social worker’s desperate request, he took in Carrington Henry, whom he was also coaching at Garfield — a clear violation were it not for Sparks’ obtaining temporary-guardian status.

Other Garfield students with unstable home lives — and some from different schools — have stayed at Sparks’ House of Champions as well, the coach setting up SAT-prep classes and college visits, trying to provide a more wholesome version of what he experienced in California.

Though he insists his Kent-based nonprofit operates within the rules, it edges toward a gray area, which may have played into Garfield Principal Ted Howard’s decision to fire the coach last year without explanation.

“They just left us”

Will Sanders had a similarly rough exit.

After Garfield’s football season ended last fall, a team booster paid for Sanders’ plane ticket back to Texas for the holidays. Once there, however, Sanders’ Seattle supporters fell away.

He said he paid his own way back and, upon arrival, learned that he’d been disenrolled.

“That was it. They just left us,” Sanders said in April, referring to himself and an athlete friend, also from Texas, also enrolled as homeless at Garfield, and also dropped from the school.

Marcus Harden, a student family advocate at Seattle’s alternative Interagency Academy, stepped in and has provided a home for both teens ever since.

The opportunity represented by high-school sports is not lost on Harden. It vaulted him to a football scholarship at Bethel College in Kansas. But he has a much more cynical view of the system now.

“Do I believe people have good intentions when they start out with this stuff? Yes, probably,” Harden said. “I don’t think anyone’s planning for kids to end up homeless. But these kids needed guidance more than they needed football.”

“What sickens me is the adults playing victim, saying they just did it to give these kids an opportunity. No, they gave themselves an opportunity.”

While participating, few students athletes see it that way.

Only in retrospect does Owens, the Garfield player from Louisiana, confess to misgivings.

Given his history of criminal involvement, Owens’ mother had suggested he move to Seattle to stay out of trouble, he said. While here, he lived briefly with his grandmother, then stayed with friends.

“It was like, ‘Here’s my chance.’ But my dreams got dropped. I was moving from home to home, sleeping on couches. And after football season ended it was like the coach didn’t care about us no more, like his whole demeanor changed. And I still ain’t graduate — that was my main motive. Now I’m just trying to get back in high school.”

During his 12th-grade year at Garfield, Owens passed just one course: history. He received a D.