Love and Trouble: A Midlife Reckoning, by Claire Dederer

This review of Claire Dederer's memoir, "Love and Trouble: A Midlife Reckoning," was published May 2017 in The Seattle Times.

Even in these confess-all times, there are secrets many of us dare not speak. Such as the difficulty of reconciling a feminist identity with the desire to be violated. Or the reality that teenage girls can be both wielders and victims of their own seductive power.

Even in these confess-all times, there are secrets many of us dare not speak. Such as the difficulty of reconciling a feminist identity with the desire to be violated. Or the reality that teenage girls can be both wielders and victims of their own seductive power.

Claire Dederer, in a ferociously honest new memoir, “Love and Trouble: A Midlife Reckoning,” walks this minefield. Most shocking of all, she does it with bracing humor.

The story begins with Dederer coming off the success of her first book, the motherhood memoir “Poser,” yet unaccountably depressed. Now a 40-something married mother of two, she mopes around her Bainbridge Island home, sucking on sour pomegranate seeds and pushing away worrisome thoughts about the sexually avaricious girl she used to be. Why, wonders Dederer, is this person suddenly resurfacing in the form of an email flirtation and attendant fantasies?

She pulls out a box of old journals to confront herself as a teenager during the 1980s, the last time she felt such wild urges. “And there she is,” Dederer writes. “That horrible girl.”

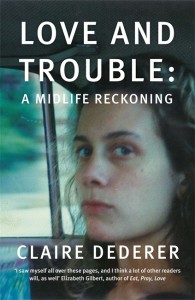

Even before readers have opened to the first page of this daring high-wire act of a memoir, they will be warned by the cover art, a close-up of the author at age 20, her sidelong gaze tough but wary. This is an unflinching exploration. Yet within that knowing face stare the eyes of a still-younger girl, challenging and bruised.

She has emerged from a 1970s childhood, one where kids were free to roam unsupervised while their parents searched for themselves. “What had previously been a fairly contained world — my mother’s Irish Catholic milieu, my father’s society Seattle milieu — was now expanding. And that was a good thing, wasn’t it? Like liberation of all kinds, including sexual liberation, this new social freedom and mobility was a good thing. Wasn’t it? For everyone. Well, maybe not for everyone. Maybe not for little girls.”

The furious heart of the book lies here, in a chapter titled “Dear Roman Polanski,” which is inspired. He materializes as a demon from Dederer’s haze of girlhood confusion, a name nagging in the back of her mind — a bogeyman, a nightmare, a mysterious, cautionary tale.

“You will never read this. Seriously. Why would you read the words of a crabby mother of two, a housewife who lives on a rural(ish) island near Seattle?” Dederer writes, mining her obsession with the infamous director and convicted child rapist, seeing in him all the contradictions of the era. “Who cares what I think? Not you, I am sure. On the other hand, Roman Polanski, as I grow older I think about you more and more often. In fact, sometimes I find I can’t stop thinking about you.”

Dederer has her own much-muted version of what befell Polanski’s victim when an adult friend of her mother’s presses himself against her in a sleeping bag — a story both skeevily specific and broadly familiar, about a particular girl on a particular night in the San Juan Islands that simultaneously echoes the experience of so many others. “Every girl has and is a history,” she notes.

Dederer, who grew up in the Laurelhurst neighborhood, has become a wry chronicler of Seattle quirk, and lovingly scrolls through a memory index of an Ave that no longer exists. This will tickle local readers, and it comes across in language hilarious enough to keep strangers interested, too.

The momentum lags slightly when Dederer recounts an ill-advised tour through Australia with a stiff, withholding boyfriend. But she is a delightfully mordant companion. You could ask for no better guide to the center of yourself.