‘Microcosm of the city’: Garfield High principal navigates racial divide

This story is part of The Seattle Times' Education Lab, a series investigating solutions in education.

Photos by Johnny Andrews / The Seattle Times

Mayor Ed Murray was firing off facts about Seattle’s divided education system, with no idea that he was standing below an area of Garfield High that students call the “black balcony.” Or that the school’s “white hallway” stretched one floor above.

Mayor Ed Murray was firing off facts about Seattle’s divided education system, with no idea that he was standing below an area of Garfield High that students call the “black balcony.” Or that the school’s “white hallway” stretched one floor above.

The selection of Garfield for a citywide education summit in April was, nonetheless, a telling choice. No other place so starkly embodies the irony of wealthy, progressive Seattle — Ground Zero for raising the minimum wage, stronghold for Bernie Sanders — presiding over a school system so undeniably segregated.

A third of the city’s white students get elite educations at private institutions, Murray noted, while a third of Seattle’s students of color attend a high-poverty school. Nearly half of all African-American and Latino students fail to graduate in four years, if at all.

“We are depriving them of the opportunity to succeed in life — we have to admit that,” the mayor said, addressing the 500 parents, educators and elected officials who had gathered for the latest attempt to focus attention on Seattle’s enduring disparities.

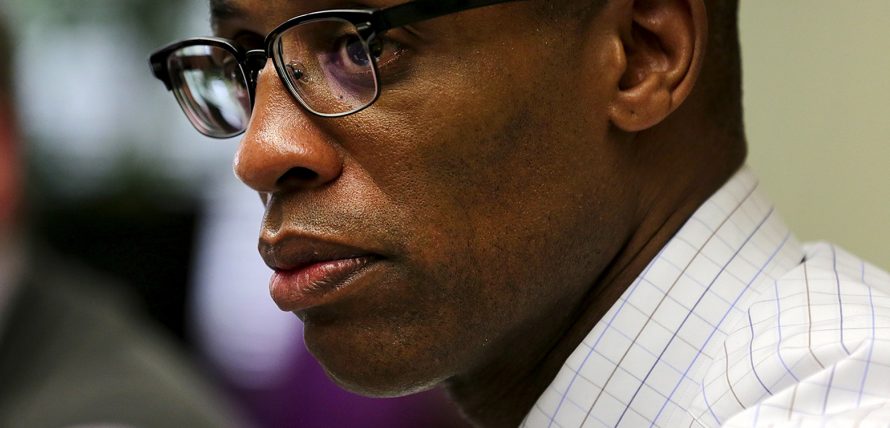

On paper, Garfield looks like a liberal utopia, a majestic, Federalist-style building in the center of the city with a broad mix of students and long history of academic and athletic success under Principal Ted Howard, a black man. Yet students of different races inhabit separate worlds. The school’s advanced-track classes are mostly white, as is its well-heeled parent fundraising group, and its annual crop of National Merit Scholars.

Meanwhile, on this year’s list of problem kids permanently removed from campus, 21 of 24 are black.

Garfield, in other words, is Seattle: a place of high achievement and deep divides, progressive ideals sitting atop uncomfortable realities.

“It’s a microcosm of the city,” said Anthony Shoecraft, education adviser to the mayor.

“At one point I thought the principal of Rainier Beach High School had the most unenviable job in Seattle,” Shoecraft said, referring to Seattle’s poorest, blackest school. “But I was wrong — it’s Ted.”

Always crisp and professional, Howard, principal since 2004, once considered his post proof that by following the rules, an African-American man could rise. But over the past three years — with police brutality and racially skewed school discipline pointing out a damaging intersection between government systems and black lives — the principal has plunged into a wrenching internal debate about public education and his place within it.

“Are we ready, really ready, to have this conversation?” said Howard, 49, reflecting on the complex realities within his building.

“Because, when I first got here a white parent told me, ‘We run this school. You’re just a caretaker, and don’t ever forget it.’ My moral objective as a black man is to protect these kids, but school-district policy, in many cases, is to expel them. So where does that leave me?”

“Throwing kids away”

Last summer Susan Craighead, presiding judge for King County Superior Court, sat in a quiet classroom at Garfield. It was a month before school, and the judge, one member of a “talking circle,” faced Howard and his two assistant principals. A county go-between thought it would benefit the educators to hear from people who encounter the effects of their decisions, particularly on discipline.

“When I walked into this room, I hated you,” Craighead, who is white, told Howard.

It wasn’t personal. She saw Howard as the embodiment of a system that seemed to know little and care less about the results of its policies.

“They’re happy to wash their hands of kids once they come to us,” the judge said in an interview.

She recalled a youth whom she’d represented as a defense attorney years ago. He was one of two boys, neither from Garfield, who’d raped a 12-year-old girl. At the time of the assault, all three kids had been suspended from school. All three were supposed to be at home, studying.

“I felt that our community, through the schools, was just throwing kids away, like the administrators had never thought about what happens afterward,” the judge said. “It’s a little like ‘not knowing’ your husband is having an affair — there’s a certain level of denial. Because if you recognize that the system is doing something bad for kids, you have an obligation to change it.”

Almost 70 percent of the students appearing in King County courts for school-related offenses are children of color, Craighead added.

Howard, too, had been wrestling with the impact of public education on black students — ever since a visit to Monroe Correctional Facility three years ago. The trip included principals from across Seattle’s historically black Central District, and its goal was to inform them about the role of school in the lives of many African-American kids.

Howard came away shaken.

He sat face to face with a former Garfield student who described teachers he could not relate to and administrators who turned a blind eye as he drifted away.

Though the inmate had attended Garfield long before Howard took the helm, the principal spent months afterward in his cramped office, poring over data. By following district rules, Howard realized, he too had pushed out hundreds of black children.

Among them: Robert Robinson Jr., who slid from foster care into Garfield with below-grade-level skills and struggled academically. After cutting class and failing to arrive at a Saturday detention, he never returned.

Robinson had been accused of petty crimes — stealing cellphones, drug use — which Howard refused to tolerate, and the rules required a parent meeting before the boy could return to school. But no one answered the phone at Robinson’s home, so he ended up several weeks later at Interagency Academy, then enrolled at Cleveland High, before being shot to death, at 17, in a drive-by on Beacon Hill.

Howard keeps the youth’s smiling freshman-year portrait on his phone, as a bitter reminder.

“I wouldn’t necessarily wave a magic wand to change things I’ve done in the past,” he said, choosing his words carefully. “But there were decisions I made and people that were hurt. That’s the part I struggle with sometimes.”

Walking a tightrope

Howard has long seen himself as a man walking a tightrope between competing interests — a strict district bureaucracy, students of vastly varied needs and parents who run the gamut from those working in the city’s most powerful offices to others with criminal rap sheets.

The main job, as he saw it initially, was maintaining harmony among them — or at least order. It seemed a natural fit. Howard is a product of Seattle Public Schools, right down to his DNA: The son of a district principal and an elementary teacher, he graduated from Garfield himself in 1985.

His father, who ran Cleveland High for more than a decade, warned that Garfield was a minefield. But the younger educator ignored this counsel, just as he would later push aside questions about the school system’s handling of black boys.

“I silenced myself,” he said. “There have been several casualties from that.”

At first, Howard patrolled the perimeter of the school with a bullhorn, shouting at kids caught hiding in the bushes. Nowadays, he strolls the hallways, on one afternoon visiting the “black balcony” and telling a group of boys to pull up their pants, ribbing a girl about her bleached-blond hairstyle — interactions far more personal than those between Howard and his white students.

Despite the extra attention, many African Americans at Garfield describe an uneasy relationship with their principal.

Three years ago, Bailey Adams accompanied her mother and older brother, Evan, to a meeting with Howard. The occasion was Evan’s suspension, for fighting.

“It was all about the rules,” said Bailey, now vice president of Garfield’s Black Students Union. “My mother was worried about Evan and college. Mr. Howard was going only by the book — he even had it out on the table, open and pointing at Seattle School District regulations. They said you could be claiming self-defense and still get suspended.”

Bailey, 16, is nonetheless sympathetic. In her view, Howard holds a near-impossible position.

“As an African-American man, people are going to be looking at you more than a white principal. So he has to go by the rules, in detail,” she said. “As an African American, someone’s going to be watching your every move.”

Hazing incident of 2013

A watershed in Howard’s gradual awakening came when he attempted to hold a large number of white students to the same standard as he does blacks.

Hazing had been an autumn tradition at Garfield for decades, and always made the principal uncomfortable. But it occurred off campus, on the wide, lush lawns of the Arboretum, and was easy to ignore — until the 2013 event, which spurred desperate emails from students; frantic phone calls from neighbors to the police; and several kids so drunk they could not walk out of the park.

Howard raced down and encountered a scene, the memory of which disturbs him still. Freshmen were staggering around, covered in hot sauce, being paddled by upperclassmen. When Howard intervened they hurled racial epithets and threw eggs. When he attempted to suspend a dozen students, all white, their families threatened legal action.

Howard had overstepped, they said. He was tarnishing their children’s college plans. He should have stayed in his office and kept his mouth shut. Several of the suspensions were overturned by the district on appeal.

The bacchanal permanently changed Howard’s settings. Nothing before had so clearly delineated the power imbalances at play in his building.

“Before the hazing, most of Ted’s decisions were based on fear. But that really beat him up, emotionally,” said Marcus Stubblefield, a longtime youth worker who first met Howard as the disciplinarian assistant principal at Franklin High. “He thought he was doing the right thing. After the Arboretum, something changed.”

Early evidence of this transformation appeared last spring, when Howard allowed school leaders to begin handling discipline through restorative justice, a method for rebuilding relationships rather than merely meting out punishment.

Then he canceled the pilot, offended that teachers had hand-picked certain students — most of them white — to lead it. Restorative justice has a place at Garfield, he believes. But, as is his habit, Howard wants to build toward it slowly.

“We weren’t ready,” he said. “Nobody’s going to be open and honest and trust, just because you put everyone in a group.”

Making plans, trying things

As he confronts the quandary of Garfield — an academic powerhouse that also must serve kids who read at a fifth-grade level, as well as 130 homeless students — Howard has decided that public education was never built for kids with needs like Robert Robinson’s.

Yet they crowd his hallways.

Part of the answer may lie in more money for counselors trained in dealing with trauma and for academic tutors. But Howard is no longer waiting. Next year he intends to abolish most out-of-school suspensions and, in response to a push from the faculty, place all ninth-graders in honors history and English, chipping away at a system that traditionally tracks gifted middle-schoolers — mostly white — into Garfield’s Advanced Placement curriculum.

Last fall, seeking to create a de facto academy for African-American boys, the principal assigned all of them to one counselor, Ray Willis, a black man who thought he could make a difference where others had not.

Parents went ballistic. Willis sat by himself on the third floor, far from the other advisers, and his work history was questionable. In 2006, he’d been fired as the girls basketball coach at Chief Sealth High School for illegally recruiting athletes.

One mother filed a federal discrimination suit (later withdrawn). But by May, eight months into Howard’s experiment, it was clear there had been no improvement. The principal’s idea had failed.

“A good intention, poorly implemented,” he says.

Growing frustration

Slowly, Howard’s deliberative style is giving way to increasing frustration and urgency. So while the mayor and Seattle Public Schools mull new initiatives dedicated to black boys’ achievement, Howard, who attended Murray’s education summit for less than an hour, views their plans with a jaundiced eye.

Dismantling a system built to sort students will take more than good intentions, he says.

“What resources are coming with this? And don’t tell me ‘It’s complicated.’ That’s just a phrase to say we are not going to deal with it,” Howard said, fuming. “It’s great to get people to the table, all fired up, but then it’s ‘We have no money.’ Really? Then why are we having this conversation?”

Many black parents are equally angry, insisting that Howard — as an emissary of the school district — has devoted his leadership to selling them out.

“A change of heart for Mr. Howard? No. Zero,” said Aaron Bossett, whose son was removed from Garfield in handcuffs in February, then spent several hours in a downtown jail cell and received a 45-day suspension for carrying a BB gun to class in his backpack.

Before that day, the youth had no significant discipline problems at Garfield. Nor did his father receive any word that four police officers had been summoned to take him away.

But the elder Bossett did get a few minutes with Assistant Principal Meghan Griffin, who told him she sympathized. As an African American, Griffin worried about her own son. But rules were rules, and the rules said a weapon in school — even a toy — meant removal by law enforcement.

“She was telling me, ‘Policy outweighs what I think is right or wrong,’ ” Bossett said. “It just amazed me because we all know these policies are toxic. We could have easily worked through some kind of discipline — because discipline was definitely needed — but not criminalization. This is a kid with no history of fighting, no gang ties. But if I can’t get this wiped off his record, it could ruin his life.”

Some supporters perplexed

Many parents, however, support Howard. They include Alec Cooper, an Amazon executive, who believes Garfield represents an essential pillar for public education in a city where so many children of means attend private school.

“It’s a very complex ecosystem and a place that, with different leadership, would crumble,” Cooper said.

Yet the principal’s style — sometimes highhanded, often aloof — continues to perplex those from his old neighborhood, down the street.

“It’s kind of like being Obama,” said Chukundi Salisbury, who graduated from Garfield one year behind Howard and has known him since both were kids. “He’s the principal who happens to be black. He’s not the black principal. He feels he has to stay above the fray.”

On the wall in Howard’s office hang large sheets of white paper listing “behavior commitments” — for himself, not students — inspired by his ongoing work with leadership coach Dan Kaufman.

“So how are you?” Kaufman asked when he walked in for their first session.

The principal answered in a two-hour monologue. He felt stuck, he told Kaufman. He was getting hit from all sides. Black parents said he was selling out their kids. Whites thought he was lax.

“I don’t know how to please any of them, and I don’t know who to please first,” he said.

At the time, every principal in the district had been assigned a mentor to work on communication and leadership. Six years later, Howard is the only one still at it.