Road Trip

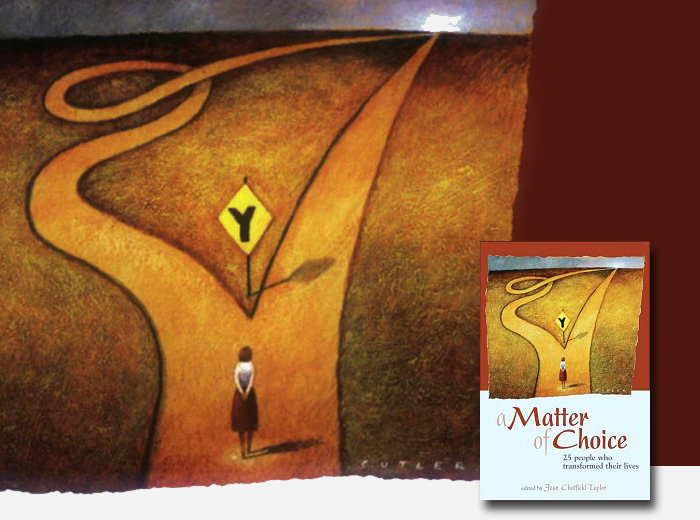

This essay first appeared in The New York Times. It was later adapted and republished in the anthology A Matter of Choice: 25 People Who Changed Their Lives. (Seal Press, 2004)

I was changing my life, leaving everyone I had ever known on the East Coast and flinging myself across the country because I wanted to try something new. A road trip, solo, seemed a suitably adventurous way to get there — more mind-expanding than flying and cheaper than shipping my belongings, I told skeptical friends.

Actually, I was dazzled by the romance of a cross-country drive. I would sail into scarlet sunsets through seas of yellow prairies. I pictured myself sitting at Western bars, talking to cowboys.

I had ideas about the Great Plains and Small Town Americana, and I had spent fifteen years as a journalist, presenting other people’s freakish, far-flung stories to the wider world. Nonetheless, I had virtually no experience of life beyond the Hudson River. Most recently, I’d been holed up in a cottage in the Catskills, scraping by as a freelance writer. Any excuse to shatter my quiet routine would have looked good, and after one summer afternoon spent ogling purple cowboy boots and the offerings at a women’s sex shop in Seattle, I was sold.

The thought of moving west had gnawed at me for the better part of a decade, ever since a brief camping trip with a tense boyfriend on the Olympic Peninsula. Our trip had metastasized into a five-year relationship that I staggered out of at thirty-five, exhausted and worn, as though I’d been walking around dead for half a decade. But I still saw snow-capped mountains in my mind.

Two years to the day of the breakup, I was packing my Volkswagen, getting ready to leave the tight little valleys of the East. People asked what I planned to do in Seattle and I could not answer. I had no clear idea — except that everything would be new.

Before setting off, however, I had to plan my route. The South suggested Gothic oddity and ghostly deserts. Very dramatic. Very Thelma-and-Louise. But I had never spent more than four hours in one go behind the wheel, and traveling that way I would have to cover three states at a single clip to make decent time. A northern path — from New York to Chicago, into the Midwestern Plains and across the Rockies — seemed the saner choice.

Only in cyberspace did I betray my misgivings.

“Are there things a woman driving alone should know?” I asked the faceless browsers at roadtripamerica.com. “Places to avoid, indispensable items to bring, reasons to turn back?”

“All you need is excitement,” the webmaster replied.

“Pepper spray,” said a friend. “At those truck stops, you’ve got to have pepper spray.”

I was determined that my trip should cost as close to nothing as possible — I had minimal savings and only vague half-leads for work on the other end — so my itinerary was based largely on the locations of people who might put me up along the way. This made Pittsburgh my first stop, and I planned to set out from Saugerties, New York, early on a sunny September morning. But road trips never begin on time — not for rock bands or families, and certainly not for freelance writers — so it was three 3 P.M. by the time my tires touched the New York State Thruway.

Most travel manuals insist you leave the interstate to find what’s left of American quirk, but on that first afternoon, even the superhighways seemed profound. I gazed at the green valleys lining I-80, thrilled by the limitless, gray asphalt unfurling before my windshield. In the rear-view mirror I scanned my life, piled neatly in the back seat: a book-in-progress and fifty pounds of attendant notes; suede jackets for every occasion; magazines I’d loved fifteen years ago and others I still planned to read; a box of cassette tapes from the 1980s, and an address book filled with the names of ex-friends. By the time I got to Pennsylvania, the rush of freedom I felt had me laughing like a madwoman.

My greatest concern about the trip had been road hypnsis, the fear that I would be lulled into a lonely sleep at the wheel. But it never happened. People kept calling on my new cell phone, rousing me from dreamy reverie.

“Where are you now?” a former boyfriend asked from his desk in Manhattan. “What are you seeing?”

I was in Indiana at that moment, racing past a tractor-trailer filled with mangy cattle who stared at me on their way to slaughter, but I told him instead about biblical sunsets and the open road. During those first few days, I got tired after four or five hours behind the wheel and tried to chat with gas station clerks wherever I could, hoping that folksy inspiration might propel me onward. At the Ernie Pyle rest stop outside South Bend, Indiana, a freckle-faced cashier was so flummoxed by these attempts at conversation that he rang up my purchases twice.

It took three days to push through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin, and I spent much of that time pondering the tidy farmhouses dotting my route. Any of them could have starred on an “America-the-Beautiful” calendar, and I wondered what it felt like to live inside a picture postcard by the side of a superhighway. I wondered if Midwesterners, so famously circumspect, had come to be that way because they felt so exposed.

Heartland uniformity shattered in Spring Green, Wisconsin, about forty-five miles west of Madison, where I stopped to see Alex Jordan’s House on the Rock, the one roadside attraction I’d planned to visit. Mr. Jordan, a medical-school dropout turned compulsive hoarder, built his sprawling monstrosity of a home upon a chimney rock as a nose-thumbing to Frank Lloyd Wright, who had once snubbed him. Then he filled his grudge-fantasia with mechanical orchestras, piles of jewels, suits of armor, cuckoo clocks, sea monsters, and antique telephones. I arrived at 4:40 P.M. on a Friday to hear from the staff that it takes five hours to properly absorb “The House,” so I tore through Jordan’s private dream world like one chased by demons.

“All by yourself?” a guard whispered in the noisy darkness.

“You’re doing very well,” another voice said as I raced past an enormous calliope.

Stone hallways hung with yellow lanterns led to caverns housing miniature circuses and village street dioramas; all of it funneling me toward a huge, clanging carousel where 239 serpents, mermaids, and satyrs spun around and around. Naked, winged mannequins floated from the ceiling. Life-sized elephants mounted each other in a pyramid. It felt like wandering through a child’s nightmare, or what we may find when Michael Jackson dies.

Afterward, I was starved and felt inexplicably dirty. Greenspirit Farm, a mile down the road, beckoned. I decided to buy a bag of apples for dinner and eat them all the way into Minnesota. An old man with a thick beard sat on a bench outside, whittling.

“When’d you leave New York?” he said, barely glancing up.

“Four days ago.”

“Where you headed?”

“Seattle,” I said. “Do you have any apples?”

“I used to live in New York!” a younger man called out, walking toward me from the vegetable barn, a blond baby attached to his hip. “Crown Heights. What street did you live on?”

Greenspirit Farm had no apples, just two farmers who wanted to talk about Woody Allen and Coney Island as the sun sank into the valley behind them. They said they’d never heard of a New Yorker leaving the city. I told them I was happy to be their first.

Dark hills framed the rest of my drive along bucolic Route 18, and in the twilight I wanted to shout out at their beauty. Then I passed a sex shop outside Rochester, Minnesota, where a fifty-foot neon sign beamed messages toward the highway — “Welcome sinners, we accept checks!”

I stayed as often as possible with friends and friends-of-friends receptive to the idea of a midlife traveler making a leap. But my presence had disquieting effects. Each morning my host or her spouse would rise early, commandeer me at the breakfast table, and whisper choked-out dreams. “All of us are living through you,” said a medievalist who put me up in Chicago.

When I craved anonymity, there was Motel 6. The franchise is supposedly aimed at road-trippers who value cleanliness and hot showers, but its cement-block walls and cigarette-scented lobbies occasionally suggested the kind of place where bad things might happen to naive girls. It was always a teenage boy with sullen eyes who buzzed me in to the front office. In Minnesota, he was flinging a pink rubber ball against the wall as I pulled out my wallet.

“I’ve made a reservation,” I said.

Throw. Thump. Catch. Somewhere, a television murmured.

“Just you, is it?” the boy said, keeping his eyes averted.

I slept poorly many nights, memories thronging my mind.

Everyone I had ever known came back to haunt me in the dark — old friends who had failed me, teachers who’d inflicted childhood humiliations. But the road washes away every indignity. You speed forward into endless horizon, and the past no longer matters. By the time I hit the waving fields of South Dakota, I was free. Doing ninety across the top of Montana, I took off my shirt and drove half-naked.

My meal plan consisted of trail mix, water, and fruit; I figured I’d arrive on the West Coast cleansed and thin. But in Glasgow, Montana, a friend-of-a-friend who worked for the State Department of Fish and Wildlife pushed a shiny breast of pheasant toward me — bagged and smoked by his hunting buddy — and suggested I make a sandwich for lunch.

“Watch out for birdshot,” he said, as I, a vegetarian for twenty-one years, hacked at the meat and smushed it between two slices of brown bread spread with horseradish.

Six hours later, I pulled the sandwich from my cooler, bit into it, and reeled. I could taste alder chips and wood smoke, the slow, deliberate preparation — and something else, something hard and small like a peppercorn. It ricocheted against my teeth and I spat it into my coffee cup with a tinny ping. Birdshot. Two Indians in cowboy hats stared at me as I zoomed past their pickup truck, heading for the mountains.

Several people had spoken reverently about Going-to-the-Sun highway, a fifty-mile stretch of road cutting across the high peaks of Glacier National Park. My bird-hunting hosts in Glasgow had insisted I drive it. But it was late afternoon, and I’d already had one flat. Thoughts of the previous night spent racing through darkness, haphazardly slaughtering various small animals that crossed my path, would not fade. And really, how breathtaking could a landscape be?

“On your way to college?” asked an aging trucker at the gas station in Shelby, Montana, eyeing my license plates and the clothes crammed roof-high inside my car.

I shook my head and laughed. College had been almost twenty years ago.

“Well, I graduated in 1996!” he crowed. “Graduated high school in 1959!”

In between, he’d supported a wife and four children by driving every road in the country. He reeled off several I might take from our gas station to Seattle.

“I was thinking, actually, of Going-to-the-Sun,” I said. “Is it worth it?”

“Beautiful,” said the trucker’s wife, poking her head out from his rig.

“Go for it!”’ he added, with a goofy thumbs-up.

I set out along a road lined with golden aspens and studied the faces of every driver headed toward me. I was looking for signs of strain, but saw only beatific smiles. I crept up forty-degree inclines, passed a glittering, glacial lake, and pulled over to touch rainbow droplets from a roaring waterfall. At the summit, I sat with two leathery bikers, staring across a misty canyon at the tips of evergreens poking from impossible precipices. Above us, the dark peaks seemed to be breathing.

The last leg of my journey followed the craterous Columbia River Gorge to the Oregon Coast. I wanted one long look at the Pacific before turning north toward my new life. On that subject, my mind was still a blank, bare as the windswept rocks lining my drive. Strangely, this inspired a surge of confidence. Nine days before, I’d stood in a friend’s living room, sobbing with fear at what might come. Fear of failure, of girlishness, buffoonery, fragility. Fear, in truth, of possibility. Now the unknown looked different. It seemed to be waving me on. I’d covered 3,800 zigzagging miles and I’d seen how much farther I could go.

It was pouring rain when I got to Oswald State Park in Manzanita, Oregon, but I sloshed down a muddy path that meandered to the sea and tromped across the sand. Sky and ocean blended into a silvery sheet and the sound of water was everywhere, trickling down the ravine, crashing onto the sea stacks, drumming from the sky.

In a grove of tall pines, a lone guitarist sat under a rickety shelter, strumming and eating oysters. He sang folk songs and offered to open a few Kumomotos for me. I tasted the brine, breathed the salt air, and tallied the last week and a half: I’d covered eleven states on thirteen tanks of gas and twenty-one large cups of coffee. I’d aged nine days but felt younger than I had in years. Two elderly women wandered up and I convinced them to try raw oysters for the first time.

My face was soaking wet, and I was changed.