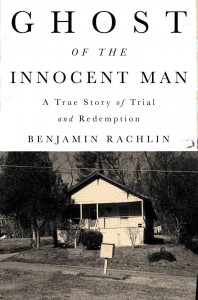

Ghost of the Innocent Man, by Benjamin Rachlin

This review of Benjamin Rachlin's examination of wrongful convictions, "Ghost of the Innocent Man: A True Story of Trial and Redemption," was published August 2017 in The Seattle Times.

Reading tales of crime today, it is difficult to remember, amid talk of DNA evidence and brain scans, just how new these forensic tools are. And, by extension, what their absence meant until very recently for hundreds of wrongfully convicted men and women.

Reading tales of crime today, it is difficult to remember, amid talk of DNA evidence and brain scans, just how new these forensic tools are. And, by extension, what their absence meant until very recently for hundreds of wrongfully convicted men and women.

That examination forms the heart of Benjamin Rachlin’s “Ghost of the Innocent Man,” which focuses on the real-life case of Willie Grimes, a gentle soul who found himself caught in a legal maze out of Kafka. Except that it was entirely American.

There is little about the opening of “Ghost” that speaks to the enormity to come. An elderly woman is raped at her home in Hickory, North Carolina, in 1987, in a scene notable mainly for its unemotional description. Grimes, 41, becomes the prime suspect, and the narrative plunges into what appears at first to be a meticulously reported procedural.

But “Ghost” is much more than that.

Grimes, a factory worker, had never been in trouble before and was so trusting of the legal system that upon hearing the police wanted to speak with him, he drove down to the station to ask why. He did not leave locked custody again for 25 years.

Sentenced to life imprisonment for first-degree rape, despite the lack of any physical evidence, Grimes remains convinced that prosecutors will realize and rectify their mistake. Months of incremental hope follow. One of the most powerful aspects of “Ghosts” is its portrait of time behind bars — the transfers, delays and letter-writing campaigns that form the scaffolding of lives in limbo.

Only after years have disappeared does Grimes finally understand:

“Obviously it did not matter that he had committed no crime. This was irrelevant,” Rachlin writes. “Possibly their convicting him had been no procedural error, to be corrected later, but an actual outcome. Possibly his imprisonment would be no exception to his life but its defining condition.”

The rest of “Ghosts” is a blinding critique of a court system all too willing to allow wrongful convictions. Not until 2001 did North Carolina pass laws requiring the preservation of evidence.

There are many such shocking revelations in this book, not least the enormous numbers of people sitting in prisons across the country who may be there improperly. After DNA testing became widely used, at least 500 were exonerated in a single decade.

“She just got the wrong person,” Grimes’ onetime girlfriend remarks casually about her own sister, who’d initially fingered him. “Everybody knows he didn’t do it.”

By this point, in 2007, the man has been wasting in prison for two decades.

Meanwhile, a network of lawyers dedicated to overturning wrongful convictions is taking root, and Rachlin braids their story with Grimes’. He finds a particularly fascinating character in North Carolina crusader Christine Mumma.

She looks nothing like the rumpled liberals in ill-fitting suits we’ve come to expect in such tales. Given to driving her Audi convertible to court when arguing speeding tickets, Mumma is a disaffected business manager who thinks studying law might be interesting. This leads to a job with the still-nascent North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence, where she works with college students, combing through letters from inmates who dispute their convictions.

It takes Rachlin 344 pages to bring Mumma together with Grimes, and at times “Ghosts” meanders into tangents. There are moments of clichéd overwriting, as when Grimes’ “every filament vibrated hideously.” Or when he feels “molten anger” about his trial.

But these missteps are redeemed by the sheer weight of information amassed. A story so important and infuriating it is hard to look away.