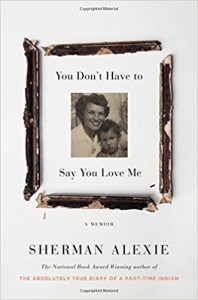

You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, by Sherman Alexie

This review of Sherman Alexie's memoir, "You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me," was published June 2017 in The Seattle Times.

Confessional memoirs are popular because, through reading about the foibles and failures of others, we tend to feel better about ourselves. It’s not the most gallant way to read a work of literature. But Sherman Alexie’s new book, “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” pulls readers so deeply into the author’s youth on the Spokane Indian Reservation that most will forget all about facile comparisons and simply surrender to Alexie’s unmistakable patois of humor and profanity, history and pathos.

Confessional memoirs are popular because, through reading about the foibles and failures of others, we tend to feel better about ourselves. It’s not the most gallant way to read a work of literature. But Sherman Alexie’s new book, “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” pulls readers so deeply into the author’s youth on the Spokane Indian Reservation that most will forget all about facile comparisons and simply surrender to Alexie’s unmistakable patois of humor and profanity, history and pathos.

His memoir is a hybrid, braiding prose passages with poems that together create the quality of a song, with story lines that ebb and return, like a chorus or fugue — the tale of Alexie’s older half-sister, Mary, who died in a house fire; the tale of his mother Lillian’s rape that conceived Mary; and the rape that conceived Lillian herself.

There is a guileless, everything-but-the-kitchen sink quality to these pages that sometimes feels as if we are leafing through Alexie’s private notebooks. We see Alexie as a boy, born brutally poor on the Spokane Indian Reservation to parents so desperate, they sometimes sold their blood for food money.

Yet now that Alexie has ascended to become a celebrated writer, a man who hobnobs with U.S. presidents and Hollywood elites, he resents being the family member with money, the one who can afford to buy his mother accommodations in a fancy retirement home.

“I felt my back spasm and ache from the heavy burden of my messiah complex,” he writes after offering to cover rent on a nearby apartment for his siblings.

By that point Alexie’s father, a gentle alcoholic, has been dead of kidney failure for 12 years. And Alexie confesses that instead of rushing to his father’s side at the end, he opts instead to go toy shopping in Seattle with his kids.

“To be blunt, I chose to leave him in the same way he had left me,” Alexie writes. “I chose to be with my wife and children — the family I had created — instead of the family I was born into.” This decision makes him a bad son, Alexie knows, but he spurns regret: “Given the chance to travel back in time, I would have still abandoned my father so I could be a father to my sons.”

Such unflinching honesty is a hallmark of this brave book. And despite its author’s evident fury — at being bullied, at social injustice, at abusive relatives — “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me” reads warmly, as if Alexie is trusting us with his deepest hurts. His mother was at the core of them all.

For many years, mother and son were estranged — refusing to speak to one another even when they found themselves in the same car. Alexie never quite explains the reasons for their rift, but Lillian’s death in 2015 spurred him to write this memoir, and her ghost continues to snipe at him, from the pages.

“You used to wet your bed,” she reminds the acclaimed author from beyond the grave. “You wet the couch until you were thirteen, I think.”

Alexie argues these facts, but the ghost retorts that he was once so shy that he refused to use a stranger’s bathroom, and so peed in his pants while waiting outside in the car.

The anecdote is classic Alexie — humiliation intertwined with humor that forms the leitmotif of this book. It’s 142 chapters, but many of them are less than a page long, which lends this memoir the feeling of a mosaic or patchwork quilt of memory.

“I am my mother’s son./I am my father’s child./And they left me a trust fund/Of words, words, and words/That exist in me/Like dinosaurs live in birds.”